OpenFace provides free and open source face recognition with deep neural networks and is available on GitHub at cmusatyalab/openface. We have a core Python API and demos for developers interested in building face recognition applications and neural network training code for researchers interested in exploring different training techniques. The neural network portions are written in Torch to execute on a CPU or CUDA-enabled GPU. See our website for a further introduction to OpenFace.

Today, I’m happy to announce OpenFace version 0.2.0 that improves the accuracy from 76.1% to 92.9%, almost halves the execution time, and decreases the deep neural network training time from a week to a day. This blog post summarizes OpenFace 0.2.0 and intuitively describes the accuracy- and performance-improving changes. Some portions assume knowledge of neural networks, like from Stanford’s cs231n class. See our release notes for a concise list of changes.

This is joint work with Bartosz Ludwiczuk, Jan Harkes, Padmanabhan Pillai, Khalid Elgazzar, and Mahadev Satyanarayanan.

The keynote of OpenFace 0.2.0 is the improved neural network training techniques that causes an accuracy improvement from 76.1% to 92.9%, which are from Bartosz Ludwiczuk’s ideas and implementations in this mailing list thread. These improvements also reduce the training time from a week to a day.

The accuracy is measured on the standard LFW benchmark by predicting if pairs of images are of the same person or of not the same person. The following examples are from the LFW data explorer.

The following ROC curve shows a landscape of some of today’s face recognition technologies and the improvement that OpenFace 0.2.0 makes in this space. The perfect ROC curve would have a TPR of 1 everywhere, which is where today’s state-of-the-art industry techniques are nearly at. See Wikipedia for more details about reading the ROC curve.

Every curve is an average of ten experiments on ten subsets (or folds) of data. I’ve included the folds for OpenFace 0.2.0 to illustrate the variability of these experiments. The OpenBR curve is from their LFW script and the others are from the LFW results page. OpenFace’s deep neural network technique lags behind the state of the art deep neural networks due to lack of data. See our “Call for Data” below if you have a large face recognition dataset and are interested in collaborating to create more accurate OpenFace models.

We obtained these accuracy improvements with a more efficient training technique. The training process first loads a model file that defines the network structure and randomly initializes the parameters. The most recent network definition can be found in nn4.small2.def.lua. The network computes a 128-dimensional embedding on a unit hypersphere and is optimized with a triplet loss function as defined in the FaceNet paper. A triplet is a 3-tuple of an anchor embedding, positive embedding (of the same person), and negative embedding (of a different person). The triplet loss minimizes the distance between the anchor and positive and penalizes small distances between the anchor and negative that are “too close.” We use Alfredo Canziani’s triplet loss implementation from Atcold/torch-TripletEmbedding.

You can mentally visualize the neural network training as points representing the embedding of images of people starting out randomly distributed on a circle. The points are the output of the neural network and are randomly distributed because the neural network parameters are randomly initialized. The training then optimizes the network’s parameters to group images of the same person together.

In reality, challenges arise because the hypersphere is 128-dimensional instead of 2-dimensional, the models have about 6 million parameters, and the training dataset has 500,000 images from about 10,000 different people (or at large tech companies, orders of magnitude more images). A crucial part of optimizing the triplet loss is in the selection stage of what set of triplets should be processed in each mini-batch. The original OpenFace training code randomly selects anchor and positive images from the same person and then finds what the FaceNet paper describes as a ‘semi-hard’ negative. The images are passed through three different neural networks with shared parameters so that a single network can be extracted at the end to be used as the final model.

Using three networks with shared parameters is a valid optimization approach, but inefficient because of compute and memory constraints. We can only send 100 triplets through three networks at a time on our Tesla K40 GPU with 12GB of memory. Suppose we sample 20 images per person from 15 people in the dataset. Selecting every combination of 2 images from each person for the anchor and positive images and then selecting a hard-negative from the remaining images gives 15*(20 choose 2) = 2850 triplets. This requires 29 forward and backward passes to process 100 triplets at a time, even though there are only 300 unique images. In attempt to remove redundant images, the original OpenFace code doesn’t use every combination of two images from each person, but instead randomly selects two images from each person for the anchor and positive.

Bartosz’s insight is that the network doesn’t have to be replicated with shared parameters and that instead a single network can be used on the unique images by mapping embeddings to triplets.

Now, we can sample 20 images per person from 15 people in the dataset and send all 300 images through the network in a single forward pass on the GPU to get 300 embeddings. Then on the CPU, these embeddings are mapped to 2850 triplets that are passed to the triplet loss function, and then the derivative is mapped back through to the original image for the backwards network pass. 2850 triplets all with a single forward and single backward pass!

Another change in the new training code is that given an anchor-positive pair, sometimes a “good” negative image from the sampled images can’t be found. In this case, the triplet loss function isn’t helpful and the triplet with the anchor-positive pair is not used.

Another major improvement in OpenFace 0.2.0 is the nearly halved execution time as a result of more efficient image alignment for preprocessing and smaller neural network models.

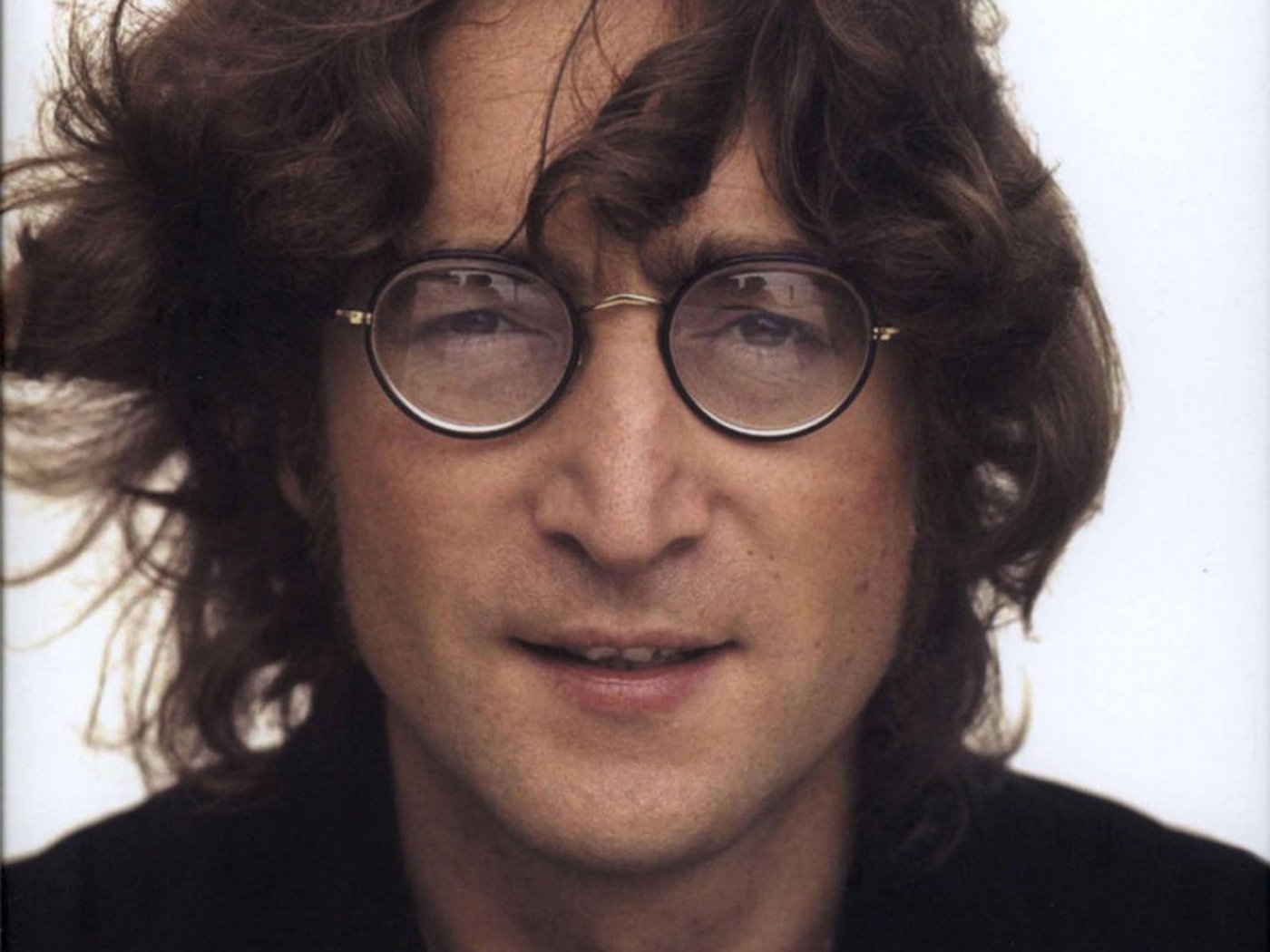

The execution time depends on the size of the input images. The following results are from processing these example images of John Lennon and Steve Carell, which are respectively sized 1050x1400px and 891x601px on an 8 core 3.70 GHz CPU. The network processing time is significantly less on a GPU.

The improvement makes the alignment time negligible and reduces the neural network execution time. OpenFace’s execution times are reduced from almost 3 seconds to about 1.5 seconds for the larger image of John Lennon, and from almost 1.5 seconds to a little over 0.75 seconds for the image of Steve Carell. These times are obtained from averaging 100 trials with our util/profile-pipeline.py script. The standard deviations are low, see the raw data.

When processing an image, face detection is first done to find bounding boxes around faces. OpenFace uses dlib’s face detector. Each face is then passed separately into the neural network, which expects a fixed-sized input, currently 96x96 pixels. One way of getting a fixed-sized input image is to reshape the face in the bounding box to 96x96 pixels. A potential issue with this is that faces could be looking in different directions. Google’s FaceNet is able to handle this, but a heuristic for our smaller dataset is to reduce the size of the input space by preprocessing the faces with alignment. We align faces by first finding the locations of the eyes and nose with dlib’s landmark detector and then performing an affine transformation to make the eyes and nose appear at about the same place.

OpenFace 0.2.0 improves the alignment process by removing a redundant face detection thanks to Hervé Bredin’s suggestions and sample code for image alignment in Issue 50. We originally performed the affine transformation to the image without resizing or cropping and then used detection a second time. OpenFace 0.2.0 reformulates the affine transformation to output an image reshaped and ready to be passed into the neural network. The following shows the logic flow for a single image that’s originally rotated that the alignment corrects.

FaceNet’s original nn4 network is trained on a large dataset with hundreds of millions of images. The following description of nn2 is from the FaceNet paper and nn4 is similar but with an input size of 96x96. The inception layers are from the Going Deeper with Convolutions paper.

The slight neural network execution time improvement is from manually

making a smaller neural network than FaceNet’s original nn4 network

with the (naive) intuition that a small model will work better with

less data since we only train with 500,000 images.

The following table compares the neural network definitions OpenFace

provides. The new networks are the small variants of nn4.

| Model | Number of Parameters |

|---|---|

| nn4.small2 | 3733968 |

| nn4.small1 | 5579520 |

| nn4 | 6959088 |

| nn2 | 7472144 |

We think further exploring model architectures will result in better performance and accuracies and are exploring automatic hyper-parameter exploration techniques. You can follow our progress on Issue 78.

Prior OpenFace versions had a Dockerfile that took a few hours to manually build. OpenFace 0.2.0 adds a Docker automated build in the Docker repository bamos/openface that continuously builds a Docker container for the latest OpenFace code. This can be used with:

docker pull bamos/openface

docker run -t -i bamos/openface /bin/bash

cd /root/src/openface

./demos/compare.py images/examples/{lennon*,clapton*}

./demos/classifier.py infer models/openface/celeb-classifier.nn4.small2.v1.pkl ./images/examples/carell.jpgThe Docker automated build worked well at first, but started timing out and failing because the OpenFace Docker image takes a few hours to build. I could have switched OpenFace to a Docker repository and manually built and pushed instead of using an automated build, but I like having the automated build so users can pull the latest version of the dependencies and code.

To significantly reduce the build times, I’ve created a Docker repository at bamos/ubuntu-opencv-dlib-torch from this Dockerfile that contains a versioned image of OpenCV, dlib, and Torch that the main OpenFace Dockerfile is based on. I build this locally so it also won’t have Docker automated build timeout issues.

The Docker automated build then doesn’t time out, works well, and

Travis was able to run tests inside of it.

However, running OpenFace in the new Docker container initially caused

Illegal Instruction (core dumped) errors in native code called from

Python from one of our libraries when running on OSX in a Docker

machine.

I don’t fully understand why we got this error, but my guess

is that building and pushing bamos/ubuntu-opencv-dlib-torch

from my Linux desktop enables non-standard compilation flags that

create binaries that aren’t able to be executed within the Docker

machine.

The current workaround to this issue is to always build and

push bamos/ubuntu-opencv-dlib-torch from a Docker machine.

Even still, this causes illegal instruction errors on some systems,

in which case the Docker containers should be built from scratch.

As OpenFace stabilizes, we’ve (finally) added automated tests for the Python API, demos, and neural network training to the tests directory. These are run on Travis here after every commit inside of the latest pre-built Docker container. A slight problem is that the latest pre-built Docker container won’t be perfectly aligned with the current Travis build. However, this is not an issue in practice since the Travis script adds the latest commit to the Docker container and the dependencies change infrequently.

The original OpenFace model is 966MB, even though it only has about 7 million float parameters. Ideally, the model should consume 7 million * 8 bytes = 20MB (!), but Torch inefficiently saves temporary buffers by default. These temporary buffers may be useful in some cases, but are not necessary in the deployed OpenFace models. There’s no official way of working around this, but from this Torch discussion from December, it looks like the Torch team is aware of this issue and still working on it. OpenFace 0.2.0 uses the third-party e-lab/torch-toolbox:Sanitize to reduce the model sizes to about 64MB!

This has been an exciting release and we’re excited to see continued OpenFace applications, improvements, and contributors. We’re always happy for thoughts on our mailing list or chatroom.

Our neural network is trained with around 500,000 images from combining the CASIA-WebFace and FaceScrub face recognition datasets, which are today’s largest available public datasets. Modern deep learning face recognition papers from Google and Facebook use datasets with hundreds of millions of images.

We believe our accuracy can be further improved with our current small-scale datasets and are exploring theoretical and engineering changes. That being said, more data usually helps with deep learning and if you have access to larger face recognition datasets with over 500,000 images and are interested in improving the models, please get in contact with me.